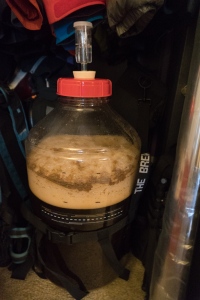

For my second brew, I wanted to attempt something similar to Westbrook’s Key Lime Pie Gose which I had the pleasure of enjoying this past summer. My goal was to brew this and have ready for the wedding… given how hot the summers can be in mid-July, it seemed appropriate.

I didn’t make any significant changes to the brewing setup, asides from a few learning lessons on the previous batch. The biggest of these was fermentation temps, since I didn’t have a way to control the last patch came out way more estery then is typical for a stout – not what I had in mind. I also wanted to pay closer attention to the sparge amount and total volumes used, trying to not come up 1gal short again.

However, the gose recipe was my first non-kit, semi-custom recipe. I found a few examples online, and based most of mine off of one in particular with a few minor adjustments. Thankfully, this one did follow a particular requirement – since this was my first attempt at a “sour” and planning to serve at the wedding (gasp!), I didn’t want to play with the unknowns of kettle souring or even less-predictable, a full-on souring in primary. The recipe called for cheating with additions of lactic acid at bottling, rather then using lacto. I figured with a gose and significant lime additions these factors would be somewhat overshadowed and less of a concern. I also did follow the idea of making a zest tincture, but instead of adding key limes to primary I juiced fresh ones and added at bottling – lest we have any flavor escaping with the CO²!

Overall, it came out fairly well. I still had problems with low volumes, problems with the pump priming caused loss of wort again (I have since built a mount for the pump to hopefully alleviate this). I added a bit too much salt at bottling, since I did it to taste. And it was a bit higher ABV then I had planned; I grabbed additional acid malt to help lower the pH in mash and accidentally added the full pound.

But my biggest surprise was the fact the key lime flavors were extremely subdued after bottle conditioning for only 2 weeks. It was certainly present, but not nearly as obvious as I was hoping for, compared to tasting at bottling. But still good. I was also more careful with ferm temps, even without a control method I made sure to cool the apartment down another 5-7 degrees to compensate.

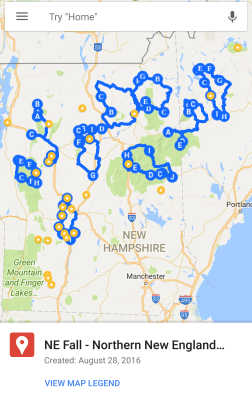

I’m planning to brew another recipe and bring it along to the wedding, why not? This one will be an NE IPA, but purchased from a kit and this time with a way to control the fermentation temps.

Hopefully it will come out well! I’m thinking about longer term brews for the fall and winter next, a cranberry pumpkin autumn brew and a big winter (maybe chocolate) Russian Imperial sound tasty. And of course, I’d love to start a real sour soon as possible considering how long they take!

It’s been a few weeks now since finally home. The Death Valley & Joshua Tree visit over Thanksgiving was awesome, but that’s about it for the travelling in the near term (except for Tahoe of course, assuming we will actually get some snow). Death Valley was quite an adventure, starting with a sandstorm blowing in as we were pulling into camp. Glad I had the Anjan with me, it was so fierce that I “slept” through an night, while a nice layer of dust was collecting on my face and small dunes were growing inside the tent. I don’t even think the REI would have survived long-term after 110 evenings this year, and even if so, it would have been even more uncomfortable.

It’s been a few weeks now since finally home. The Death Valley & Joshua Tree visit over Thanksgiving was awesome, but that’s about it for the travelling in the near term (except for Tahoe of course, assuming we will actually get some snow). Death Valley was quite an adventure, starting with a sandstorm blowing in as we were pulling into camp. Glad I had the Anjan with me, it was so fierce that I “slept” through an night, while a nice layer of dust was collecting on my face and small dunes were growing inside the tent. I don’t even think the REI would have survived long-term after 110 evenings this year, and even if so, it would have been even more uncomfortable.